A Tale of Three Chargers

Within a few minutes of my home is a busy freeway exit, the turn off point for three EV charging options. Their usage patterns tell you everything you need to know about what drivers actually want – and what we’re getting wrong about charging infrastructure.

Option one: A renowned family rest stop just two minutes from the exit. The kind of place that’s been serving fresh baked goods for generations – eat in or take out – with a petting zoo that draws families from across the region. In the parking lot sit two Plunk EV Level 2 chargers. Free to use. True plug-and-charge: pull in, connect, no app required, no payment screen, no account creation. Just plug in and go enjoy a butter tart while the kids feed the goats.

Option two: One minute from the same exit, a flashy refurbished development anchored by the original, now upgraded, gas station convenience store, next to a Tim Hortons with a drive-through. Two DC fast chargers – Level 3, the kind that get all the infrastructure funding and policy attention. Premium speed. Premium price.

Option three: Down the hill in the actual community; the local arena has a Level 2 charger. Pay-to-use model – app required, account setup, the usual friction.

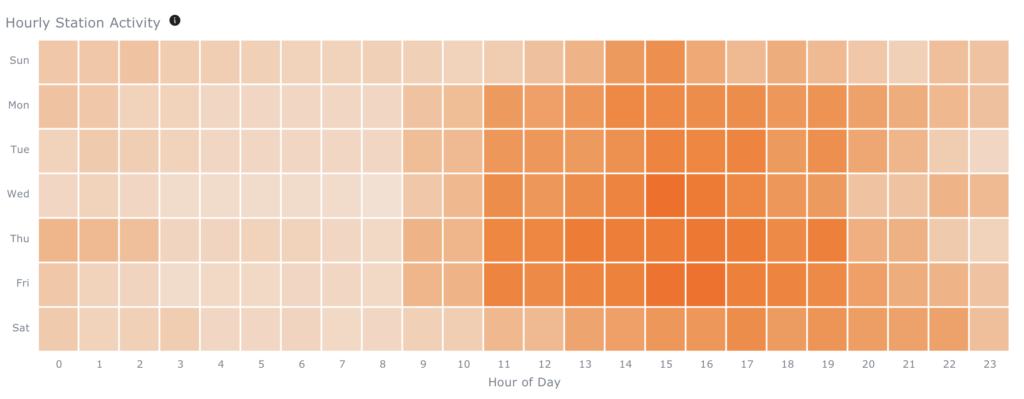

Here’s what I observe: the Plunk EV chargers at the bakery are almost always in use. The DC fast chargers at the gas station? Empty. The arena charger? Empty.

This isn’t an anomaly. It’s a pattern that reveals something fundamental about what EV drivers actually need – and how badly we’ve misread that need by obsessing over speed.

The fast chargers sit unused because they’re designed for a use case that barely exists: the desperate driver, battery nearly depleted, racing to get back on the highway. They’re the emergency room of charging infrastructure – essential for the rare crisis, irrelevant for daily life.

The arena charger sits unused because friction kills adoption. An app to download. An account to create. A payment method to register. For what – thirty kilometres of range while watching a hockey game? The hassle exceeds the benefit.

The bakery chargers thrive because they understand something the others don’t: charging should be incidental to living your life, not an interruption of it. You’re already stopping for butter tarts. The kids already want to see the animals. The charger is just there, asking nothing of you, adding value while you do what you came to do.

Free. Frictionless. At a destination you’d visit anyway.

This is everywhere charging in miniature. And it points toward a completely different model than the one we’ve been building.

Extending the Analogy

If battery storage represents the emergence of savings accounts and grid-scale installations function as institutional reserves, EV charging infrastructure introduces another layer to the energy banking system. And here, the distinction between Level 2 and Level 3 charging maps onto a familiar divide in financial services: the credit union versus the high-frequency trading floor.

Level 3 DC fast chargers are the flashy option – the financial equivalent of algorithmic trading platforms. They move large amounts of energy quickly, serve transient users, and require massive capital investment and grid infrastructure. They’re designed for highway corridors and high-throughput commercial locations. They serve people passing through.

Level 2 chargers are different. They’re slower, cheaper, and designed for places where vehicles dwell – homes, workplaces, community centres, bakeries with petting zoos. They integrate with daily life rather than interrupting it. They’re the community credit union: less glamorous, more accessible, and fundamentally oriented toward serving local members rather than maximizing transaction volume.

The gas station with its DC fast chargers is trying to replicate the old model: a dedicated refuelling destination where speed is the value proposition. The bakery with its Level 2 chargers has stumbled onto the new model: charging as an amenity, invisible and incidental, woven into places people already want to be.

For First Nations communities – and for under-served communities generally – this distinction has profound equity implications.

The Infrastructure Economics

Level 3 charging requires grid infrastructure that doesn’t exist in many communities.

A single DC fast charger draws 50-350 kW. A charging station with multiple Level 3 units can demand a megawatt or more – equivalent to adding a small industrial facility to the local grid. This requires:

- High-voltage utility connections (often requiring distribution system upgrades)

- Dedicated transformers rated for massive peak loads

- Demand charges that can exceed $10,000-$20,000 monthly regardless of utilization

- Three-phase power that may not be available in residential or rural areas

Those empty fast chargers near my highway exit? Their operator is paying demand charges whether anyone uses them or not. The business model depends on high throughput that isn’t materializing – because the use case they’re designed for is rarer than the infrastructure funding assumed.

For remote First Nations communities on isolated diesel grids, Level 3 charging is often physically impossible without generator upgrades that would increase diesel dependence – precisely the opposite of the intended outcome. For grid-connected rural communities, the utility upgrade costs can exceed the charger costs by an order of magnitude.

The financial analogy holds: high-frequency trading requires expensive infrastructure – direct exchange connections, co-located servers, sophisticated software. It’s accessible to Goldman Sachs, not to community credit unions. Level 3 charging is similar: it requires infrastructure investments that only make sense for highway corridors with guaranteed high throughput, or for well-capitalized commercial operators with utility cooperation.

Level 2 charging works with existing infrastructure.

A Level 2 charger draws 7-19 kW – comparable to an electric stove, a dryer, or a small workshop. Most residential and commercial electrical services can accommodate Level 2 charging with minimal or no upgrades. The infrastructure requirements are:

- Standard 240V electrical service (already present in most buildings)

- A dedicated circuit and breaker (routine electrical work)

- The charger itself ($500-$2,500 for equipment, plus installation)

The bakery near my highway exit didn’t need a utility upgrade to install its Plunk EV chargers. It just needed an electrician for a day. The chargers probably cost less than the espresso machine inside.

For communities with constrained electrical infrastructure – whether remote microgrids or aging rural distribution systems – Level 2 charging fits within existing capacity, especially when paired with smart charging that shifts load to off-peak hours or coordinates with local solar generation.

The credit union analogy: you don’t need a trading floor and fiber-optic connections to serve local depositors. You need a secure building, competent staff, and relationships with the people you serve. Level 2 charging is community-scale infrastructure for community-scale needs.

The Usage Pattern Alignment

Level 3 charging serves a use case that’s rarer than we assumed.

DC fast charging exists because people making long trips need to replenish quickly and continue. The model assumes:

- Drivers arriving with depleted batteries needing rapid turnaround

- High vehicle throughput to justify capital costs

- Premium pricing to cover infrastructure and demand charges

- Transient users who won’t be back for months or years, if ever

This is the highway rest stop model – and it has a role for inter-city travel. But the empty fast chargers near my exit reveal the flaw: most EV drivers most of the time don’t need emergency rapid charging. They need convenient, low-friction top-ups at places they’re already going.

The Tim Hortons drive-through next to those empty fast chargers is full of gasoline cars. Their drivers stop for coffee, not fuel. The EV drivers who might stop for charging don’t need the speed – they need the destination to be worth visiting. And a gas station parking lot isn’t it.

Level 2 charging aligns with how people actually live.

Most vehicles sit parked for 20+ hours daily. They’re at home overnight. At work during the day. At the bakery for a half-hour treat. At the arena for a two-hour hockey game. At the community centre for a meeting.

Level 2 charging turns these dwell times into charging opportunities. A vehicle plugged in at the bakery for 30 minutes gains 15-20 km of range – not enough for a road trip, but plenty for the kind of daily driving most people actually do. A vehicle at the arena for a full game gains 40-50 km. A vehicle at home overnight gains 150+ km.

The Plunk EV chargers at the bakery succeed because they’re in a place people want to be. The dwell time is a feature, not a bug. You’re not waiting to charge; you’re enjoying butter tarts while charging happens invisibly.

The arena charger fails despite being Level 2 because friction kills the value proposition. The dwell time is there – two hours of hockey – but the app and payment hassle make it not worth bothering. Remove the friction and that charger would see the same success as the bakery.

The Friction Factor

My local example illustrates something the infrastructure planning models miss: friction matters more than speed.

The Level 3 chargers offer speed but nothing else. No destination worth visiting. No reason to be there except charging. And if you don’t desperately need a fast charge, there’s no reason to stop.

The arena charger offers a great destination – community life, kids’ activities, local connection – but buries it behind friction. App download. Account creation. Payment setup. For occasional use, the hassle exceeds the benefit. So people don’t bother.

The bakery chargers offer both: a destination worth visiting and zero friction. Plug in, walk away, enjoy your visit. The charging is incidental. It asks nothing of you.

This is the formula: destination plus frictionlessness. Speed is irrelevant if you’re spending an hour at the bakery anyway. Payment friction is fatal even at a great destination.

For First Nations communities designing charging infrastructure, this insight is crucial. The arena, the health centre, the band office, the community hall – these are natural destinations where people already spend time. Adding Level 2 chargers to these locations works if and only if the charging is frictionless. The moment you introduce apps and payment terminals, you’ve killed the value proposition.

The bakery figured this out, probably not through sophisticated analysis but through intuition: make it free, make it simple, make it invisible. People will come for the butter tarts. They’ll leave with a charged vehicle. Everyone wins.

The Equity Implications

Level 3 infrastructure investment flows to highways and urban centres.

Because Level 3 charging requires high throughput to be economically viable, investment gravitates to locations with guaranteed traffic: highway corridors between major cities, urban commercial districts, big-box retail parking lots. These locations are, almost by definition, not in First Nations communities – particularly not in remote or rural communities.

My local fast chargers sit at a highway interchange serving Toronto-to-cottage-country traffic. That’s the target market: affluent urban EV owners making recreational trips. The community down the hill – the actual town where people live and work – gets a friction-laden Level 2 charger that nobody uses.

Federal and provincial EV infrastructure funding has disproportionately supported Level 3 deployment along major routes. This makes sense for enabling inter-city travel, but it means charging infrastructure investment bypasses the communities that most need transportation cost relief.

The financial parallel: bank branches close in rural and Indigenous communities because transaction volumes don’t justify the overhead. ATM networks thin out. Payday lenders fill the gap with extractive services. The communities most in need of financial services get the least access.

Level 3 charging deployment follows the same pattern. The infrastructure goes where the traffic already is, not where it’s most needed.

Level 2 infrastructure investment can go directly to communities.

Level 2 chargers cost a fraction of Level 3 installations – often 5-10% of the total project cost. For the price of one DC fast charging station, a community could deploy 20-40 Level 2 chargers at homes, workplaces, and community facilities.

This fundamentally changes the equity calculation:

- Lower capital requirements mean projects are achievable with available grant funding

- Distributed deployment means benefits reach individual households, not just people who can reach a central location

- Local installation work creates community employment rather than requiring specialized external contractors

- Integration with home solar and battery storage compounds benefits across the energy system

The credit union model: instead of one flashy downtown branch, you have accessible services distributed throughout the community. Instead of requiring customers to come to you during business hours, you meet them where they are.

The bakery model applied to a First Nations community: chargers at the band office, the health centre, the school, the arena, the community hall, the elders’ centre. Free. Frictionless. At destinations people already visit. Charging woven into daily life rather than imposed as a separate errand.

The Integration Opportunity

Level 2 charging integrates with residential battery storage.

This is where the energy banking analogy becomes most powerful. A home with solar panels, battery storage, and a Level 2 EV charger operates as an integrated energy system:

- Solar generates during the day

- Battery stores excess for evening household use

- EV charges overnight from stored solar or off-peak grid power (or overnight generation in diesel communities)

- Smart systems optimize across all three based on rates, solar availability, and vehicle needs

This integration is technically straightforward with Level 2 charging because power flows are manageable and timing is flexible. The EV becomes another form of energy storage – a mobile battery that can (with V2G capability) feed power back to the home or grid during emergencies.

Level 3 charging, by contrast, is a brute-force injection of energy that doesn’t integrate gracefully with home-scale systems. It’s a transaction, not a relationship.

For a company deploying residential or community batteries, Level 2 charging is the natural complement.

The same customer relationship, the same installation visit, the same electrical panel, the same monitoring and optimization platform. Battery and charger work together as a system, managed holistically. The company provides integrated energy services rather than point solutions.

Level 3 charging is a different business entirely: commercial real estate, utility negotiations, network roaming agreements, payment processing for transient users. It requires different capabilities, different capital structures, and different customer relationships. For a company focused on residential deployment in First Nations communities, Level 3 is a distraction at best, a misallocation of resources at worst.

The Vehicle-to-Grid Dimension

V2G is practical with Level 2 infrastructure.

Vehicle-to-grid – using EV batteries to provide power back to homes or the grid – requires bidirectional chargers and extended connection times. The vehicle needs to be plugged in, with sufficient battery reserve, for long enough to provide meaningful services.

Level 2 charging aligns perfectly with this requirement. Vehicles plugged in at the bakery for an hour, at the arena for two hours, at home overnight – these connection windows enable V2G participation. The power flows are modest enough to integrate with residential electrical systems and community microgrids.

Level 3 charging is fundamentally incompatible with V2G. Vehicles at DC fast chargers are there for 20-45 minutes, trying to get back on the road. There’s no dwell time for grid services. The infrastructure is designed for one-way energy transfer at maximum speed.

For First Nations communities – especially remote communities where local resilience matters – V2G capability through Level 2 charging adds a layer of value that Level 3 cannot provide. A community’s parked EVs become a distributed battery reserve, available to support critical facilities during outages or generation shortfalls.

The energy banking analogy: Level 2 with V2G enables your vehicle to participate in the local energy economy – depositing energy when you have surplus, withdrawing when you need it, earning “interest” by providing grid services. Level 3 is a pure withdrawal: fast, transactional, uninvolved in the community’s energy system.

The Resilience Argument

Level 3 infrastructure is a single point of failure.

A community that depends on a single DC fast charging station has a single point of failure. If that station goes down – equipment failure, utility outage, network issues – no one charges. If it’s the only fast charger in the region, vehicles can be stranded.

Those empty fast chargers near my highway exit? When they’re out of service – which happens – there’s no backup for anyone who was counting on them limping in with only a 5% SOC. A gas station model’s fragility, replicated in electrons.

This vulnerability is particularly acute for remote communities where the next alternative might be hundreds of kilometres away.

Distributed Level 2 infrastructure is inherently resilient.

Twenty Level 2 chargers spread across a community have twenty times the redundancy. If three fail, seventeen still work. If the grid goes down, chargers connected to solar-plus-storage systems may continue operating. The failure of any single unit is an inconvenience, not a crisis.

The bakery chargers go down occasionally. Nobody panics. There are other options – or you just come back tomorrow. The system is resilient because it’s distributed.

For communities that have experienced the fragility of centralized infrastructure – diesel generators that break down, transmission lines that ice over, utility systems designed for someone else’s priorities – distributed resilience isn’t an abstraction. It’s essential.

The Behavioural Fit

Level 2 charging requires – and rewards – planning.

Critics sometimes frame Level 2’s slower speed as a limitation. But for regular daily use, it’s actually an advantage: it encourages and rewards integration with daily life. You stop at the bakery because you want butter tarts; the charging is a bonus. You go to the arena because your kid has hockey; you leave with more charge than you arrived with.

This behavioural shift – from dedicated refuelling trips to ambient charging throughout the day – changes the relationship with energy. You’re no longer a customer making transactions at a retail point; you’re a participant in an ongoing energy system. This aligns with the broader energy banking transition: from point-of-sale transactions to ongoing financial relationships.

Level 3 charging replicates the gas station experience.

DC fast charging is designed to feel like a gas station: drive in, plug in, wait, pay a premium, drive away. It preserves the behavioural model of internal combustion vehicles – which may ease the transition for some users but foregoes the deeper benefits of electrification.

The empty fast chargers at the gas station near me are trying to sell a gas station experience to people who bought EVs partly to escape gas stations. The value proposition is confused.

For First Nations communities building new transportation patterns around electrification, Level 2 offers the opportunity to establish charging-as-life as the norm from the start, rather than replicating the gas station model with its associated costs and dependencies.

The Cost-Per-Kilometre Reality

Level 3 charging is expensive for users.

DC fast charging typically costs $0.35-$0.50/kWh or more in Canada – three to five times residential electricity rates. Demand charges, equipment costs, and lower utilization all get passed through to users. For frequent use, Level 3 charging erodes much of the fuel cost savings that make EVs attractive.

Level 2 charging, especially when free or low-cost, is dramatically cheaper.

Home Level 2 charging at residential rates costs $0.08-$0.15/kWh in most Canadian jurisdictions – sometimes less with time-of-use optimization. The free Plunk EV chargers at the bakery cost exactly nothing for drivers to use.

With home solar or free community charging, marginal charging costs approach zero. For diesel-dependent communities currently paying $0.50-$1.00/kWh for electricity, solar-charged EVs represent transformative transportation cost savings even before considering free charging at community destinations.

A driver charging primarily at Level 2 – some at home, some at free community chargers like the bakery – might pay $0.02-$0.05/km for electricity or less. This is the economic transformation that electrification promises, but it’s only realized with affordable, accessible charging infrastructure.

For First Nations communities where transportation costs consume a disproportionate share of household budgets, this difference is material. Level 3 charging at premium rates doesn’t deliver the transformation. Distributed Level 2 – especially free community charging at destinations people already visit – does.

The Business Case for Level 2 Focus

For a company serving First Nations communities with residential battery storage and EV charging, the case for Level 2 focus is clear:

Alignment with core capability. Residential battery installation and Level 2 charger installation use overlapping skills, equipment, and customer relationships. Level 3 deployment is a different business.

Achievable project economics. Level 2 projects fit within available grant funding and community capital capacity. Level 3 projects often don’t.

Integration value. Solar, battery, and charger work together—solar charges the battery by day, the battery charges the EV by night, smart controls optimize the whole system. Integrated deployment captures value that piecemeal installation misses. Level 2 enables integration; Level 3 doesn’t.

Community-scale deployment. Twenty Level 2 chargers across a community – at the band office, the health centre, the arena, the school, the store – create more access, more resilience, and more equity than one Level 3 station at the highway interchange.

V2G pathway. Level 2 infrastructure positions communities for V2G participation as vehicles and technology mature. Level 3 infrastructure doesn’t.

Recurring service relationships. Community chargers create ongoing relationships – monitoring, maintenance, optimization, eventual upgrade. Level 3 stations serve strangers passing through.

The bakery model scales. What works at a butter-tart shop works at a band office. Free, frictionless, at destinations people already value. That’s the template.

What the Bakery Knows

The family that runs the bakery near my highway exit probably didn’t commission a study on EV charging infrastructure models. They didn’t analyze Level 2 versus Level 3 economics or model dwell-time utilization rates.

They just understood something intuitive: people come here because they love this place. If we make it easy for EV drivers to charge while they’re here, they’ll come more often and stay longer. The chargers cost less than the petting zoo fence. Why not?

That intuition – charging as hospitality, as amenity, as community service rather than commercial transaction – points toward a completely different infrastructure model than the one dominating policy conversations.

The gas station with its empty fast chargers is trying to sell speed to people who have time. The arena with its friction-laden charger is trying to extract payment for a service people don’t value enough to hassle with. The bakery is just making charging easy and getting out of the way.

One of these models is working. The others aren’t.

For First Nations communities building energy sovereignty, the lesson is clear: be the bakery, not the gas station. Build charging into places people already want to be. Make it free if you can, frictionless regardless. Let charging disappear into daily life.

The infrastructure that gets used is the infrastructure that serves people. Everything else is just equipment for a ribbon-cutting photo … and then the crowd moves on to the next shiny object.